Part 6

Previous Page | Introduction | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

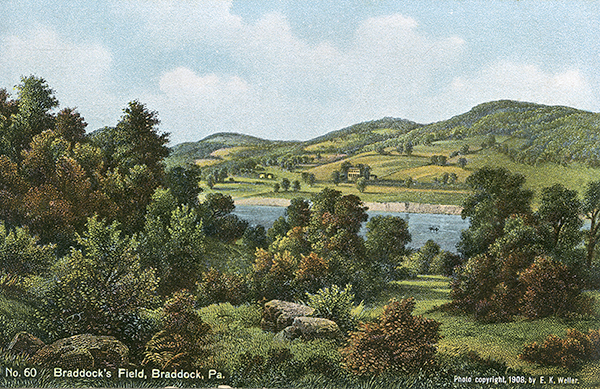

From Washington Springs the line follows the course of the present road for about a mile, with distinct marks at intervals along the sides; it then continues in a northerly direction eastward of the present road to a point east of Jumonville and of Jumonville's grave.[57] From here it keeps its northerly course along a very narrow crest of the mountain, past the Honey Comb Rock, and thereafter in the main follows the dividing line between North Union and Dunbar townships to a point about one mile south of the old Meason house on the Gist Plantation, when by a slight deflection northwestward it crosses Cove Run and the Pennsylvania Railroad to Gist's Plantation, the place of the eleventh encampment.[58] Between the tenth and eleventh encampments the traces of the road are so plain that one does not have to rely on inference. The last mountain barrier had now been passed.

|

Dunbar's Knob, Jumonville, Pa. Dunbar's regiment formed their forward and final encampment on a flat piece of ground in close proximity to a fine spring near the reservoir of the Soldiers' and Orphans School, and within a few hundred yards of the spot where Washington the year before had defeated the French forces under Jumonville. On June 27 Braddock marched rom Fort Rock (See No. 38) to Gist's Plantation, passing nearby the scene of Jumonville's defeat and to the east of Dunbar's Knob. [Lacock] |

| |

|

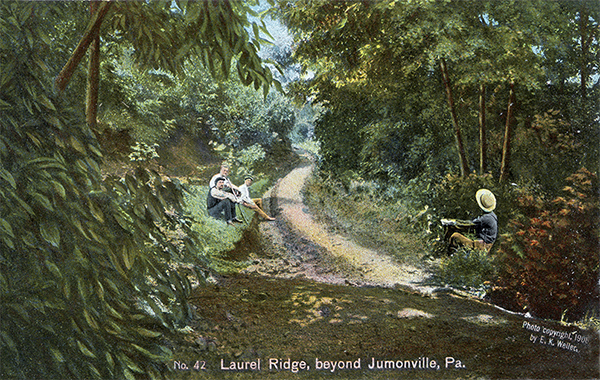

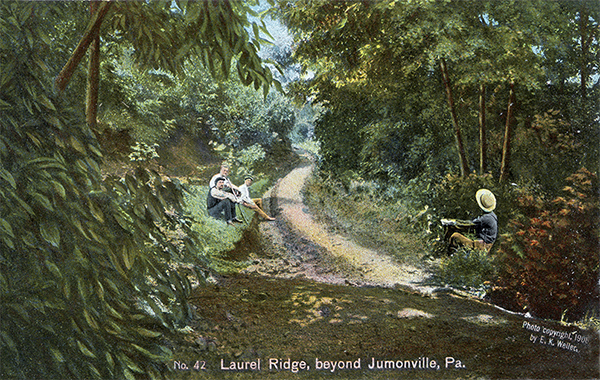

Laurel Ridge, beyond Jumonville, Pa. The road from Jumonville follows the crest of Laurel Ridge. This is a scene on the ridge south of the Honey Comb Rock about three miles from Jumonville. [Lacock] |

| |

|

Laurel Ridge, near Mt. Braddock, Pa. This is a view on the northern slope of Laurel Ridge about two miles south of Mt. Braddock. Braddock's Road on Laurel Ridge from Jumonville to Mount Braddock, roughly speaking, follows the course of the township line between North Union and Dunbar townships. [Lacock] |

Along this narrow road, cut but twelve feet wide and with the line of march often extending four miles at a time, the army had toiled on day after day, crossing ridge after ridge of the Alleghany Mountains, now plunging down into a deep and often narrow ravine, now climbing a difficult and rocky ascent, but always in the deep shadow of the forest. On such a thoroughfare, running between heavily-wooded forests on either side of the road and made still narrower and often several feet deep by usage, it was of course impossible for a vehicle coming in the opposite direction to pass; but on nearly all the mountain ranges, and especially in the low grounds, there were wider places where by some kind of signals or by some preconcerted understanding the packtrains and wagons, which frequently moved in caravans, could meet and pass one another. Thenceforward, however, the character and general aspect of the country were noticeably different. The land of active coal developments, including coke ovens, had been reached. For many miles to the northward the traveller passes over a vast extent of country from under which the coal has been taken, and from which the props have given way in many places, leaving deep and treacherous holes. Such crevices are especially frequent from Prittstown to a point east of Mount Pleasant, a circumstance which in some places materially interferes with the relocation of Braddock Road.

|

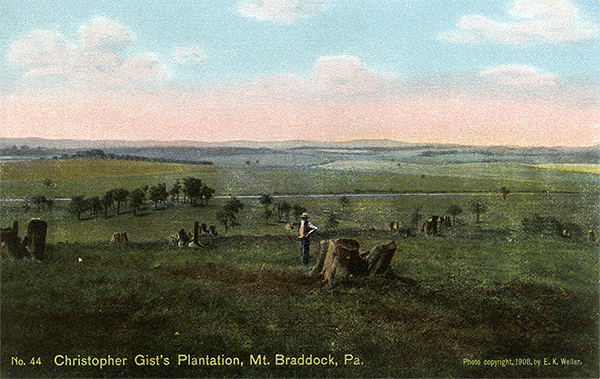

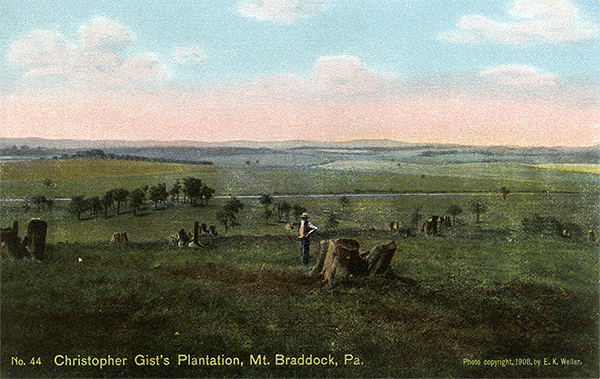

Christopher Gist's Plantation, Mt. Braddock, Pa. This plantation, formerly consisting of 2500 acres of land, later known as the Mount Braddock farm, is very beautifully situated. Washington, the previous year had cut a road over Laurel Hill to Gist's plantation, and threw up some intrenchments near a fine spring. General Braddock marched to Gist's plantation on June 27, 1755, and there encamped - the eleventh encampment. Mt. Braddock is very near the geographical center of Fayette county. [Lacock] |

Leaving Gist's Plantation the line runs abruptly to the northward, evidently keeping the higher ground to a point about a quarter of a mile east of Leisenring, where it turns into the valley of Opossum Run and follows the stream to its mouth in the Youghiogheny. On the west side of the Youghiogheny, near Robinson's Falls, was the place of the twelfth encampment.[59] Although no trustworthy scars of the road from Gist's Plantation to this point are discernible, there can be little doubt that this was the line of march.[60]

|

Robinson Falls, near New Haven, Pa. A short distance from the mouth of Opossum Creek, just west of New Haven, these beautiful falls may be seen. A short half mile below New Haven was the 12th encampment - "the camp on the east (west) side of the Youghiogheny," on lands formerly of Colonel William Crawford, later Daniel Rogers. [Lacock] |

| |

|

Stewart's Crossing, (Youghiogheny), Connellsville, Pa. The army crossed the Youghiogheny below Connelsville, a little to the north of the mouth of Opossum Creek to a point on the opposite side of the river near the mouth of Mounts Creek. The fording of the river on June 30, 1755, was about 200 yards broad and about three feet deep. [Lacock] |

Braddock forded the Youghiogheny at Stewart's Crossing, below the mouth of Opossum Creek, to a point on the opposite side of the river above the mouth of Mounts Creek, half a mile below Connellsville.[61] His next encampment, which was on the east side of the fording, a mile north of the mouth of Mounts Creek, cannot be definitely fixed; but most probably it was on Davidson's land, southeast of the Narrows.[62] Between this point and the battleground there were still some highlands to be crossed, which, though trivial in comparison with the mountains already traversed, were yet rugged enough to present serious difficulties to the troops, already worn out with previous labors and exertions.

|

| Braddock's Old Stone House, Connellsville. |

From the camp the road passes through the Narrows, evidently along the present township road, until it strikes the boundary line between Bullskin and Upper Tyrone townships. This it follows in a northeasterly direction for a distance of some mile and a half, with a few noticeable deflections from the present township road, to a point about half a mile east of Valley Works. Here the course veers away to the northeast in almost a straight line to Prittstown, either paralleling or coinciding with the line between Bullskin and Upper Tyrone for the last mile or so. Then, continuing in the same direction beyond Prittstown for a mile and a half, it reaches the John W. Truxell farm (recently purchased by Elmer E. Lauffer[63]), where on the night of July 1 the army seems to have bivouacked in order that a swamp which extended for a considerable distance on either side of Jacob's Creek might be made passable. From the Truxell farm the line turns almost due north through the swamp, crossing Green Lick Run, and thence keeping a straight line west of the Fairview church to a point a short distance west of Hammondville. Here, at a place called Jacob's Cabin, still on the east side of Jacob's Creek, the army encamped. It must be admitted that very few reliable traces of the road from Connellsville to this point were found by the exploring party; but the topography of the country, the course of the road as shown on the earlier maps, the testimony of Orme's journal and of local tradition, all lead the writer to believe that the route between these two points as here laid down is correct in the main.[64]

|

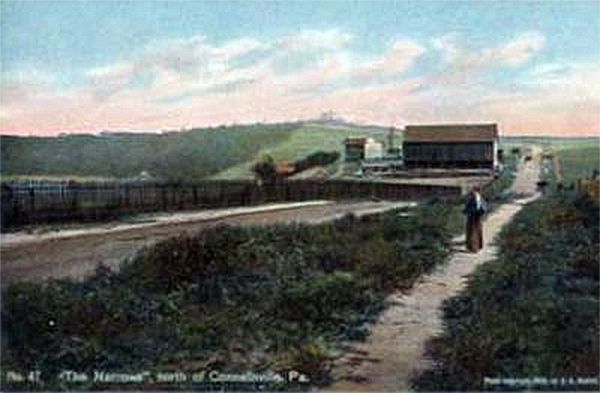

The Narrows, north of Connellsville, Pa. Captain Orme says: "we were obliged to encamp about a mile on the west (east) side where we halted a day to cut a passage over a mountain." This "mountain" of which he speaks is a high bluff known as "the narrows." The thirteenth encampment - "the camp on the west (east) side of the Youghiogheny," was about a mile from the mouth of Mounts Creek. [Lacock] |

Braddock appears to have crossed Jacob's Creek a short distance west of Pershing Station, on the Scottdale branch of the Pennsylvania Railroad near the spot where Welshonse's mill formerly stood.[65] On this side of the creek the road follows the township line a distance of one and one-half miles to Eagle Street in Mount Pleasant, and while still within the limits of the town crosses the Pittsburg and Mount Pleasant pike. From Mount Pleasant the course for the next few miles is quite evidently that of the township line between Mount Pleasant and Hempfield townships on the east and north and East Huntingdon and South Huntingdon townships on the west and south respectively. A portion of this line coincides with the road now in use. About a mile north of Mount Pleasant is a very deep scar in an old orchard on the John McAdam farm, a trace which continues to be visible for some rods farther north on the same farm. A little way beyond the point where the Braddock Road leaves the McAdam farm there is also a marked depression for over five hundred yards on the property of the Warden heirs. Extending a mile westward from the intersection of the Mount Pleasant, Hempfield, and East Huntingdon township lines is a great swamp of several hundred acres,[66] which the road skirts to the eastward and then keeps on to the Edwin S. Stoner farm, near Belson's Run, a tributary of Sewickley Creek. According to local tradition, this farm is the site of the Salt Lick Camp, a view in support of which there is much to be said.[67]

|

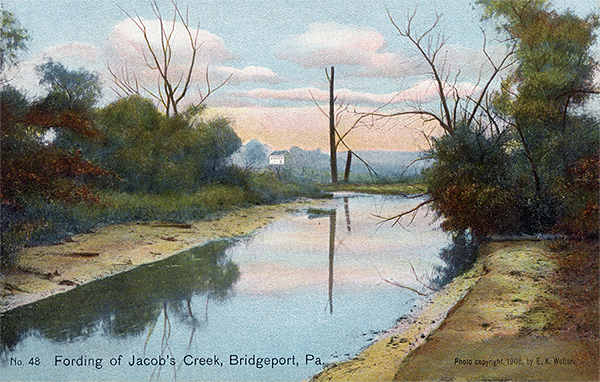

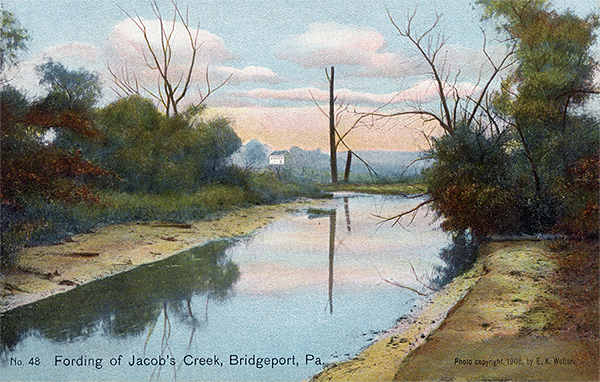

Fording of Jacob's Creek, Bridgeport, Pa. The crossing of Jacob's Creek was a short distance above Pershing Station on the Scottdale Branch of the P.R.R. near a point where Weichbanse's mill formerly stood. The fording of the creek was well chosen by reason of the great swamp which extends for several miles along Jacob's Creek. The fourteenth encampment, or rather the bivouac, - the "Great Swamp," was on the east side of Jacob's Creek. [Lacock] |

| |

|

Union Springs, Mount Pleasant, Pa. The Braddock or Union Springs are situated in Mount Pleasant on the property of Mrs. Elizabeth Shield Hitchman, a short distance from the corner of Spring and Eagle streets. Two magnificent streams of water gush forth near an old spring house. That either of the advanced or rear guard of Braddock's army may have bivouaced at or near the springs seems not wholly unlikely. So string a supply of most delicious spring water could not but attract the attention of moving squadrons. [Lacock] |

| |

|

Braddock's Lane, near Hunkers, Pa. South of Cambato's store, and south of Belson Run, is a stretch of Braddock's Road, practically abandoned called Braddock Lane. This is a short distance southeast of Hunkers. (See No. 51) [Lacock] |

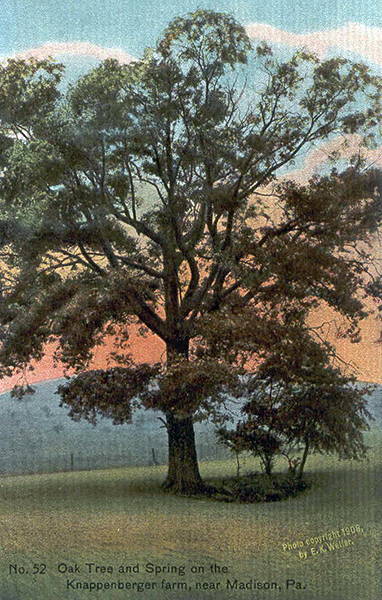

About a quarter of a mile from the Stoner farm the line crosses Belson's Run southeast of Combato's store to a private or secondary road known as Braddock's Lane, which it follows for three-quarters of a mile till it meets a township road. From this point it keeps the present township line to Sewickley Creek, at the point of intersection between Hempfield and South and East Huntingdon townships, half a mile southwest of Hunkers.[68] After crossing Sewickley Creek[69] the road veers away northwest, showing a slight depression a little farther on, south of David Beck's house. Continuing in practically the same straight line, it apparently joins the boundary line between Sewickley and Hempfield townships, and thence runs westward along this line to the D. F. Knappenberger farm,[70] which offers all the requirements favorable for a camp, and is probably the place of the sixteenth encampment, Thicketty Run.[71]

|

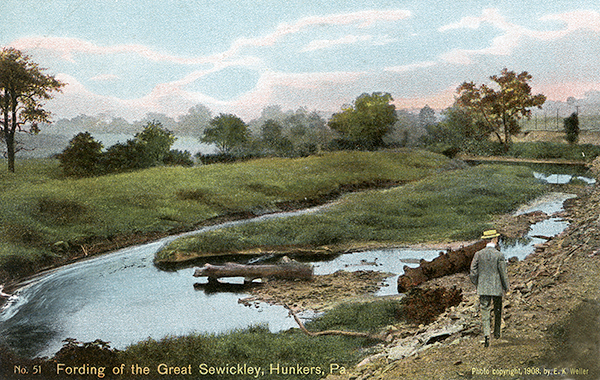

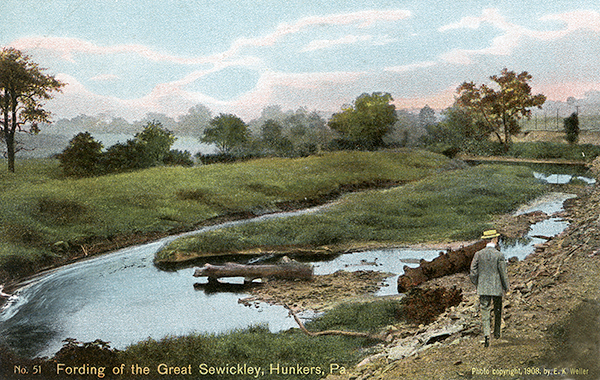

Fording of the Great Sewickley, Hunkers, Pa. The fording of the Great Sewickley (formerly known as Gowdy's or Goudy's ford) was about one-fourth mile below Hunker. A short distance north of Hunker were formerly located Painter's Salt Works; and a short distance south of Hunker were the well know salt licks. In earlier days great herds of stock were brought to these salt wells which were drilled to a depth of 450 to 500 feet. [Lacock] |

| |

|

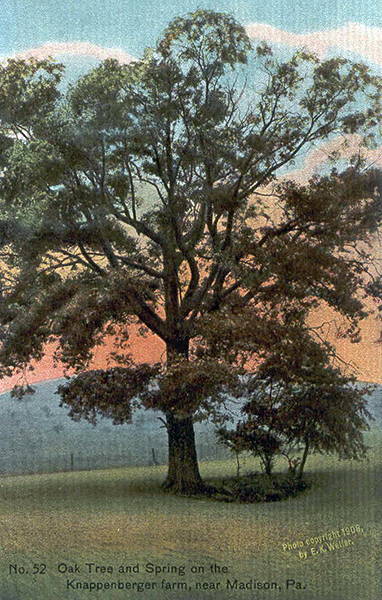

Oak Tree and Spring on the Knappenberger Farm. This beautiful tree and spring are situated on the D. T. Knappenberger farm about midway between Hunker and old Madison. The local tradition is that Braddock encamped on this farm. There is some evidence which would seem to support this claim. [Lacock] |

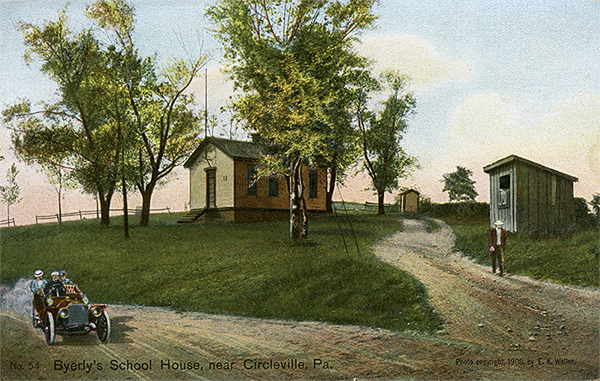

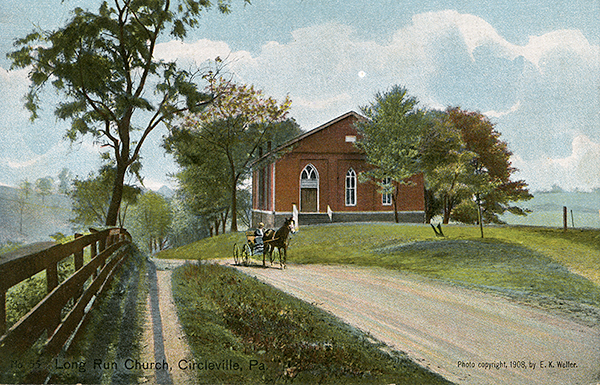

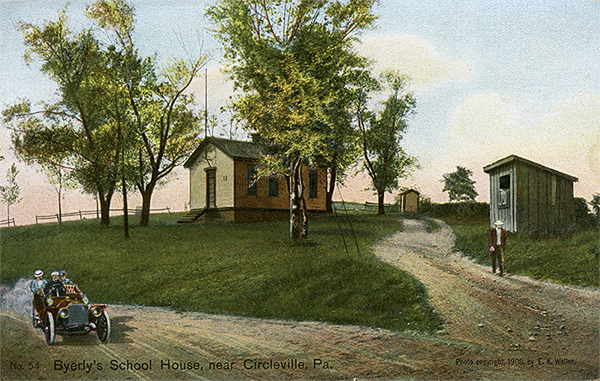

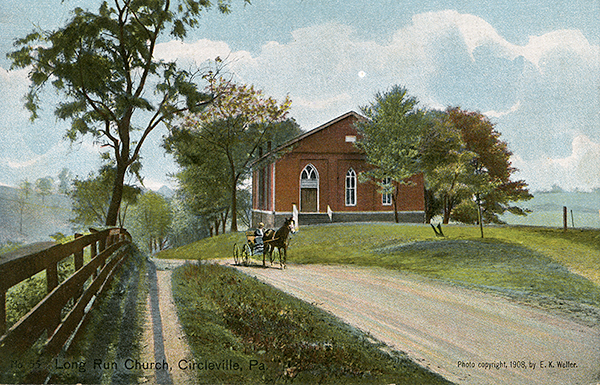

From this place, which is about a mile southeast of old Madison, the road seems to follow the township line northwestward; for southwest of Madison there are some well-marked scars, and a short distance beyond the town, near the fording of a run on the higher ground approaching the Little Sewickley, there are more traces. After fording the Little Sewickley it passes, still northwestward, through the John Leisure farm,[72] showing on the top of the hill beyond and west- ward toward the John C. Fox if arm some trustworthy scars. At this point, about a mile northwest of the Little Sewickley, it crosses a township road over some falls between John C. Fox's house and barn, and thence with very perceptible traces keeps on in the same straight line to the William B. Howell farm. From a point one-fourth of a mile southeast of the Howell house it follows the present clay road to a point as far beyond, and thence continues westward to the Hezekiah Gongaware farm.[73] After leaving this place the line is unquestionably that of the present township road for about a quarter of a mile; then, going on in the same direction, it passes about a quarter of a mile south of Byerly's schoolhouse. At less than half a mile beyond the schoolhouse it joins the present township road again, and thus continues to Circleville, except for one short stretch of a few rods to the east of the road, where there is a very clear depression. In Circleville the road seems to pass east of Long Run church, and a few rods northwest of it crosses the Pittsburg and Philadelphia turnpike. Here, in the neighborhood of Circleville and Stewartsville, the army encamped again.

|

Falls on the John Fox Farm, near Herminie, Pa. From old Madison to the John Fox farm, Braddock's Road follows pretty closely the township line between Sewickley and Hempfield townships. These falls on the John Fox farm are less than one mile northeast of Herminie. The local tradition is that the road originally passed over these falls. [Lacock] |

| |

|

Byerly's School House, near Circleville, Pa. About one and a quarter miles southeast of Circleville is Byerly's School House. The course of the road to this point, the topography of the country, and a scar in a field near by, lead one to believe that the road passed less than one-fourth mile east of this school house. (See No. 55) [Lacock] |

| |

|

Long Run Church, Circleville, Pa. The road at Circleville passes east of Long Run Church. Braddock halted or encamped in the neighborhood of Circleville, Jacksonville and Stewartsville. On July 8 Braddock, after halting one day, turned almost at a right angle into the valley of Long Run at or near Stewartsville. While there are no trustworthy scars of the road at this place of encampment, yet the course of the road can be followed out approximately. (See No. 54) [Lacock] |

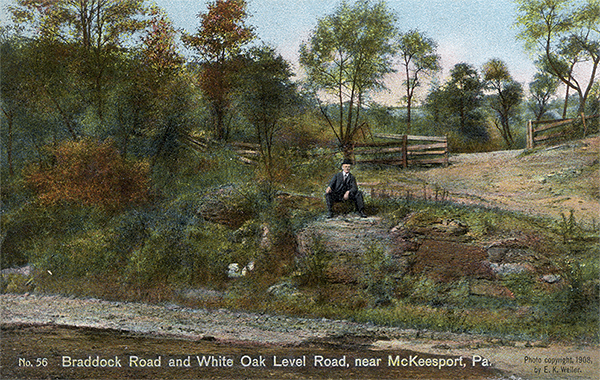

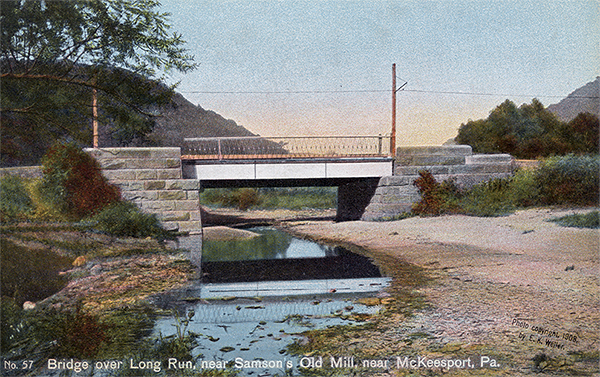

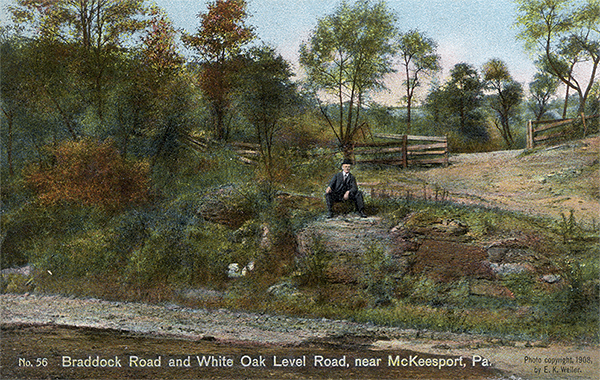

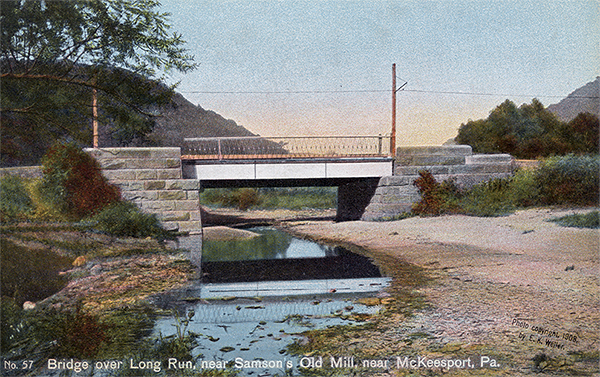

At this point General Braddock, after causing an examination of the country between the camp and Fort Duquesne to be made, abandoned his design of approaching the fort by the ridge route, being deterred by the deep and rugged ravines of the streams and by the steep and almost perpendicular precipices to the eastward of Circleville and Stewartsville.[74] Turning westward, therefore, at almost a right angle at or near Stewartsville, possibly at Charles Larimer's barn, the route strikes out in a shorter line coincident with the present county road, undoubtedly following the course of this road for about a mile; thence continuing in the same direction for a little over a mile along a ridge on either side of which is a narrow valley, it intersects the White Oak Level road about half a mile east of the boundary line between Alleghany and Westmoreland counties. From this point it follows naturally down the valley of Long Run, past what was Samson's old mill,[75] and across Long Run at or near the present bridge to a point about two and a half miles westward where the army encamped at a very favorable depression now known as McKeesport, two miles north of the Monongahela River and about four miles from the battlefield. A magnificent spring of water marks the site of this encampment, which was called Monongahela Camp.[76]

|

|

| |

|

Braddock Road and White Oak Level Road, near McKeesport, Pa. This photograph shows the point at which Braddock's Road, coming coming off the high ground from Stewartsville, intersects with the White Oak Level Road, about one-half mile east of the boundary between Westmorland and Allegheny counties. The route from Stewartsville to this point was well chosen. It seems that the road did not follow the valleys one either side of this higher ground, as some are disposed to claim. (See No. 55) [Lacock] |

| |

|

Bridge over Long Run, near Samson's Old Mill, near McKeesport, Pa. Less than one and one-half miles distant from the point at which Braddock's Road intersects the White Oak Level Road in the Valley of Long Run, the bridge over this run is reached. A few hundred yards west of this bridge was formerly situated Samson's Old Mill. [Lacock] |

| |

|

Braddock Spring, McKeesport, Pa. This spring is situated on a lot in McKeesport owned by Mrs. Elizabeth Bennett, a short distance from the corner of Bennett Avenue and Braddock Street. Here, July 8, 1755, Braddock encamped. Washington, who had taken seriously ill at or near Little Crossings, two miles west of Great Meadows, joined Braddock, at this, his last encampment before the Battle at Braddock's Field. [Lacock] |

| |

|

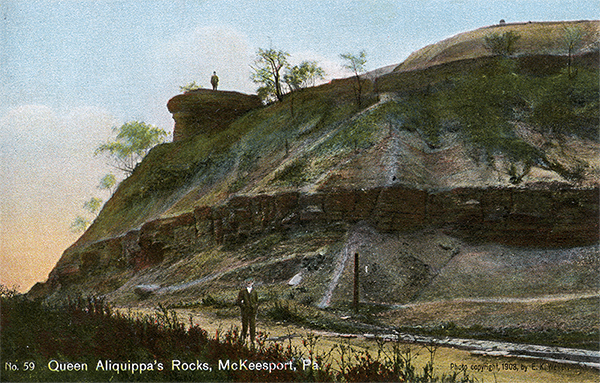

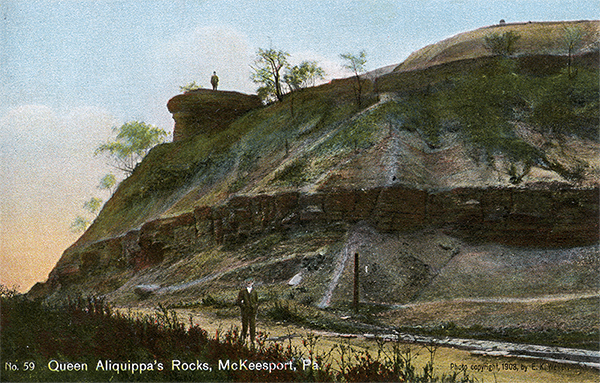

Queen Aliquippa's Rocks, McKeesport, Pa. On the morning of July 9, Braddock turning into the valley of Crooked Run, crossed the Monongahela, at or near the mouth of this run. Queen Aliquippa who lived at the confluence of Youghiogheny with the Monongahela, the present site of McKeesport, is said to have advised Braddock not to proceed against the French. [Lacock] |

On the morning of July 9 the army turned into the valley of Crooked Run down what is now known as Riverton Avenue, fording the Monongahela to the north of the mouth of the run in order to avoid the narrow pass on the east side of the river.[77] The route follows down the western bank of the Monongahela through what is now Duquesne, fording the river a second time a short distance west of Turtle Creek. Here, on the eastern bank of the Monongahela, the battle took place. From a point about a mile southeast from Circleville to Braddock's Field there are no trustworthy scars of the road; but the topography of the country is such that the line between these two points can be readily determined. Some of the older citizens pointed out to the writer the place at which Braddock forded the Monongahela, for marks of the passage have been visible until within a few years.[78] Recently, however, the whole complexion of the ground on the west side of the river has been changed to so great a degree, not only by the erection of steel works with their large deposits of slag along the banks, but also by the improved methods of navigation, that all traces of Braddock's movements are forever obliterated. On the eastern side of the Monongahela and west of Turtle Creek, at what is now Braddock, where the battle occurred, encouraging efforts are now on foot that promise to lead to a satisfactory settlement of the point at which the fording actually occurred, as well as of the location of the route through the battlefield and of the ground on which the British and the French troops took position.[79]

|

Map of the battlefield at the start of the battle. Click here to display a high resolution version of this map. |

| |

|

Map of the battlefield at 2 pm. Click here to display a high resolution version of this map. |

| |

|

| Map of the Braddock Battlefield. Click here to display a high resolution version of this map. |

| |

|

| A map of the Battle drawn by an Indian warrior. Click here to display a high resolution version of this map. |

| |

|

| Another map of the Braddock Battlefield. Click here to display a high resolution version of this map. |

In the hope of finding some signs of the path through the battlefield, the writer made a somewhat careful examination and study of the place; but the contour of the ground over which the line of march extended was found to be so much altered that even the slightest traces of its course were not perceptible. From a study of the Mackellar maps,[80] however, it would appear that from a point a few rods west of Turtle Creek, eastward and northward of Frazer's Cabin, the road veered away to the northwest,[81] evidently crossing the Pennsylvania Railroad at or near Thirteenth Street (where there was formerly a hollow way or ravine, it is said), and thence more than probably following the course of the railroad to Robinson Street, and on to a point northward of the old Robinson burying-ground. From here the line would seem to have kept east of the Pennsylvania Railroad and station until it reached a point about six hundred yards beyond the station, between Jones Avenue and Sixth Street. This street may be identified as the second ravine, through which Frazer's Run flowed and in which the advance column of Braddock's army was attacked by Captain Beaujeu[82] and his party.[83]

Footnotes

[57] Jumonville marks the northernmost point reached by Dunbar's regiment. Near the grave is the ledge of rocks on which Washington and the Half King took position in their attack on Jumonville, May 28, 1754, in what proved to be the initial battle of the French and Indian War. As Francis Parkman tersely puts it, 'This obscure skirmish began the war that set the world on fire' (Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, 1905, I, 156).

[58] Orme Journal, 344.

[59] Orme Journal, 344. James Veech says in his Monongahela of Old (p. 60) that this encampment was 'a short half mile below New Haven,' on land then (1858) owned by Daniel Rogers; but Judge Veech is confused by Orme's entry of June 28, which says, 'The troops marched about five miles to a camp on the east [west] side of Yoxhio Geni' (Orme Journal, 344). It is worthy of note that Orme uses the term 'the troops marched' and not his customary phrase 'we marched,' a circumstance from which it seems reasonable to infer that the advance column halted a day at this encampment, and that on June 29 the officers and the rest of the army at Gist's Plantation joined it here.

[60] See Shippen's drafts, to which reference has already been made. Through the courtesy of J. Sutton Wall, chief draughtsman of the Interior Department, Harrisburg, Pa., who has made a draft connecting a number of tracts lying southward from Stewart's Crossing along the line of Braddock Road to Gist's place and the foot of Laurel Ridge, the writer has been greatly aided in the preparation of his own sketch. In the connected draft a few of the tracts do not show the road; but a sufficient number do show it to corroborate the conclusions reached by him relative to the course of the road from Gist's place to Stewart's Crossing, and hence to enable him, on the accompanying map, to lay down the road between these two points with greater accuracy.

[61] Olden Time, II, 543; Veech, The Monongahela of Old, 60-61.

[62] Orme Journal, 345; Veech, The Monongahela of Old, 61.

[63] Mr. Truxell writes to me, under date of November 30, 1908, that his farm has been owned by the Truxells since 1806, and that in the course of his life he has ploughed up at least a quart of bullets, sometimes as many as a dozen at a single ploughing.

[64] In regard to Braddock's movements on July 1st and 2d, the writer desires to offer a plausible solution of some statements in Orme's journal that have led to no little confusion and inaccurate assertion on the part of those who have written on the subject.

'On the first of July,' says Orme, 'we marched about five miles, but could advance no further by reason of a great swamp which required much work to make it passable.' This bivouac, as has already been said, is undoubtedly on the farm of John Truxell. The army, which was dose at the heels of the advance or working party, had to halt there till a corduroy road could be thrown across the swamp a process that required time. 'On the 2d July,' continues Orme, 'we marched to Jacob's Cabin, about 6 miles from the camp.' Notice the words 'from the camp.' The preceding stop was then a bivouac, not a camp. The camp referred to was the encampment one mile on the east side of the Youghiogheny, at Stewart's Crossing. This day's march would be about one mile, and the place of encampment Jacob's Cabin. The two halting places were evidently both on the east side of Jacob's Creek. What is commonly known as the Great Swamp Camp was only the bivouac to which reference has been made.

This view of the matter seems, however, not to have been taken by any of the cartographers: but in estimating the value of maps one must, of course, consider whether the author's first-hand knowledge, as well as his borrowed data, be trustworthy or not, and must also take into account the purpose for which the map was made. Professor Channing has pointed out among other things that, while 'a lie in print is a persistent thing,' one on a map is even less eradicable, and for three reasons: (1) because the historical evidence on maps is liable to error, and an error once made is copied by other cartographers, with the result that a false impression frequently continues through centuries; (2) because the topography is often wholly wrong, especially on the earlier maps, a fact that is too commonly overlooked by historians; (3) because, as our own national history has abundantly proved, boundaries are frequently delineated imperfectly, inaccurately, and without basis in fact. In a word, Professor Channing thinks that maps are often taken too seriously, that the historical information given by them is liable to error, and that they simply raise a presumption.

It is certainly true that, judged by the exceedingly accurate and reliable journal of Orme, the map accompanying Sargent's History of an Expedition against Fort Du Quesne (op. 282) is in almost every in stance wholly inaccurate in regard to the location of Braddock's camps, which it represents as scattered promiscuously along the route. In scarcely a single respect, indeed, whether as to route or as to location of camps, mountains, rivers, or anything else, can it be depended upon. To cite a single instance, it puts Camp 6 (Bear Camp) on the Youghiogheny, when this, as we have seen, is the location of Squaw's Fort . No clue to the authorship of this map or to any authority for it can be discovered. Similar fallacies occur in the work of one of our latest historians, E. M. Avery, who in his History of the United States and its People (Cleveland, 1904, IV, 67) also prints a beautifully-colored but inaccurate map. Judge Veech, too (in his Monongahela of Old, 61), recognizes an apparent inconsistency in Orme's journal at this point; but, like the others, he only adds more fuel to the flame of confusion.

[65] Veech, The Monongahela of Old, 61. Only a small part of the foundation of this mill is now to be seen.

[66] Jacob's Swamp. This is not to be confused with the swampy land along Jacob's Creek.

[67] It is only fair to say, however, that there is lunch difference of opinion in regard to the location of this camp. On July 3 Orme records, 'The swamp being repaired, we marched about six miles to the Salt Lick Creek.' Many of the later maps and later accounts of the period identify Jacob's Creek with Salt Lick Creek (see Sargent's History, 346; Veech's Monongahela of Old, 61; Scull's map, 1770, etc.); but there is no real authority for holding that the Salt Lick Creek mentioned by Orme is Jacob's Creek. A small tributary of the Youghiogheny, now known as Indian Creek, was, it is true, formerly called Salt Lick Creek, whence came the name of Salt Lick township; but the well-known salt licks and Painter's Salt Works were located along the banks of Sewickley Creek near Hunkers. Here salt wells used to be drilled to a depth of about five hundred feet; and to these wells stock was driven from miles around, and people came from far and near to boil down the salt water in order to secure salt for domestic use. In the absence, therefore, of any authoritative evidence that the Salt Lick Creek mentioned by Orme is Jacob's Creek, it seems to the writer that the most probable location of Salt Lick Camp is on the Edward Stoner farm, about two miles east from the fording of Sewickley Creek. Among other indications that point to this farm as a favorable place for encampment one notes the fact that a short distance west of the Stoner house, under a large oak tree, there was formerly an excellent spring (now welled up), and that there is also a run near by. Mr. Stoner showed me a one-pound cannon ball which he found in a stump less than a quarter of a mile from the road, and said that other bullets had been picked up on the farm.

[68] Eugene Warden, Esq., of Mount Pleasant, Pa., has aided the writer very materially in the location of the road through Westmoreland County by calling his attention to the following document, which establishes definitely the fording of Jacob's Creek and the course of the road to Sewickley Creek.

'The Commissioner of Westmoreland County, pursuant to the directions of an Act of Assembly of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, entitled 'An Act for laying out competent Districts for the appointment of Justices of the Peace, passed April 4, 1803,' laid out the said county into the following districts, to wit: . . .

'Huntingdon South: 'Beginning at the mouth of Big Sewickley; thence up the river Youghiogheny to the mouth of Jacob's Creek; thence up said creek to Braddock's Fording; thence along Braddock's Road to Mt. Pleasant District line to a corner of Hempfield District; thence along said line to Big Sewickley; thence down said creek to the place of beginning.' (Court of Common Pleas of Westmoreland County, Pa., Continuance Docket No. 5, p. 443.)

[69] This fording was called Goudy (or Gowdy) Ford.

[70] See Orme Journal, 346.

[71] On July 4 Orme writes, 'we marched about six miles to Thicketty Run.' This day they would cross Sewickley Creek a short distance west of Hunkers, and their most likely place of encampment would he on the D. E. Knappenberger farm, about two miles south of the fording, on Little Sewickley Creek or Thicketty Run. This solution, which makes Salt Lick Creek the Sewickley Creek and Thicketty Run the Little Sewickley Creek, is no mere whim of the writer, but has been reached from a knowledge of the country supplemented by the topographic sheets and by a reasonable interpretation of Orme's Journal. If he in correct in his reasoning·, there is no inconsistency in Orme's account.

[72] Now owned by a coal company.

[73] According to the distance travelled from the preceding camp, the seventeenth encampment, or Monacatuca Camp, would be on this farm; but, according to local tradition it was on the William R. Howell farm, a mile away. This is the one camp as to the location of which the writer has been unable to arrive at a satisfactory conclusion. Considering the lay of the land, however, he sees no good reason why the army should not have made the distance mentioned by Orme.

[74] Judge Veech is in error when he says that the road 'crossed the present tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad and turnpike west of Greensburg' (Veech, The Monongahela of Old, 62). The railroad is beyond this precipice. On this point see Orme Journal, 351.

[75] Only a millstone is left to mark the location of the old mill.

[76] The spring is situated on a lot owned by Mrs. Elizabeth Bennett, a short distance from the corner of Bennett Avenue and Braddock Street. Washington, who had been left at Bear Camp, joined Braddock here.

[77] Orme Journal, 352. Mr. Wall of Harrisburg communicated to me a copy of a draft of a survey made July 29, 1828, on 'Application No. 2169,' showing the location of the road down Crooked run (Braddock nun) to the Monongahela and across it to a point a short distance beyond. This fording of the river is often designated Braddock's Upper Ford.

[78] On file in the Department of Interior Affairs is a 'Map and Profile for a slackwater navigation along the Monongahela River from the Virginia Line to Pittsburg as examined in 1828 by Edward E. Gay, Engineer,' which shows Braddock's Upper Riffle at the mouth of Crooked Run, and Braddock's Lower Riffle at the mouth of Turtle Creek.

[79] G. E. F. Gray, chief clerk of the Edger Thomson Steel Works at Braddock, Pa., wrote to me under date of December 9, 1908, that their chief engineer, Sydney Dillon, had already done some preliminary work toward locating the original banks of Turtle Creek and of the Monongahela River, and toward fixing the place of Frazer's Cabin and of the road through Braddock. The steel works are 1ocated on a part of the battlefield, along the river.

On February 11, 1909, Mr. Dillon communicated to me the results of his labors based on a study of the ground in connection with the two maps made by Patrick Mackellar, Braddock's chief engineer (Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe, 1905, I, op. 214-215), supplemented by the plan in Winsor's Narrative and Critical History of America, V. 449, and by the Carnegie McCandless Company's property map of 1873. This is by far the most able and careful study of the battlefield that has been made in modern times. Mr. Dillon's plans enable one to follow the course of the road through the battlefield, and to form an idea of the action with a distinctness that has not been possible heretofore. In order to comprehend the nature of the fight, however, and to understand the conditions that made Braddock's defeat almost inevitable, one must see the field for himself.

[80] On the two plans of the battlefield drawn by Patrick Mackellar, see Parkman, Montcalm and Wolfe (1905), I, 229, n. 1.

[81] See maps, ibid., op. 214-215, and in Sargent's Expedition against Fort Du Quesne, op. 219.

[82] Hyacinth Mary Liénard de Beaujeu.

[83] If the course of the road as thus indicated be correct, then the thickest of the fight would have been east of the Pennsylvania Railroad between Thirteenth and Sixth Streets, the location of the Hollow Way and of Frazer's Run respectively. The writer was told that when the Pennsylvania Railroad built its roadbed through the battlefield it unearthed a great number of human skeletons, a circumstance which, if true, would seem to confirm his conclusion as to the ground on which the principal fighting took place. Mr. Dillon seems to think that the Hollow Way was between Ann and Verona Streets, and that the farthest point reached by Braddock's party was across the ravine near Corey Avenue. Another view is that the course of the road never extended above or east of the Pennsylvania Railroad, but stopped a few rods short of it in the Robinson burying-ground.

[84] [Brusca note: This is from an 1854 painting by Paul Weber.]

Previous Page | Introduction | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

View user comments below.