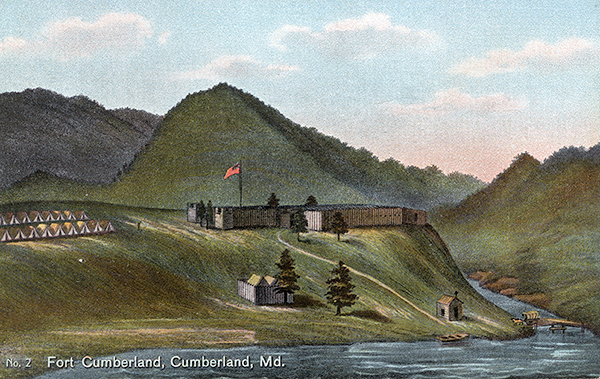

Part 2

Previous Page | Next Page | Introduction | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

Of Braddock's relations with the Indians there are many conflicting stories; but a careful examination of the most trustworthy accounts will convince an impartial investigator that there is no basis in fact for the charge, often made, that his conduct toward them was impolite and unjust. On the contrary, it is difficult to find a single fair criticism that can be made against him on this score. However one may account for the circumstance that eight of them accompanied the expedition, it seems to be practically certain that this small number was not due to the fact that the Indians had not received very reasonable consideration from the English General.

In providing the horses, wagons, and supplies necessary for the undertaking, Braddock was assisted by Benjamin Franklin, whose extraordinary efforts, tact, and courage called forth his warm appreciation. "I desired Mr. B. Franklin, postmaster of Pennsylvania, who has great credit in that province," he wrote on June 5, "to hire me one hundred and fifty wagons and the same number of horses necessary, which he did with so much goodness and readiness that it is almost the first instance of integrity, address, and ability that I have seen in all these provinces."[6]

In the solution of his third problem, that of constructing a road through Pennsylvania in order to have an adequate avenue for securing supplies, Braddock was less successful. He quickly recognized the importance of having a road cut west of the Susquehanna in order to intersect with the route of the army at a place called indifferently Turkey Foot, Crow Foot or the three forks of the Youghiogheny (at what is now Confluence[7]); and he had the satisfaction of seeing the work of building his road prosecuted with great diligence by Governor Morris of Pennsylvania. Unfortunately for Braddock, it proved to be impossible to complete the road in time for it to be of any service to him in the expedition.[8]

|

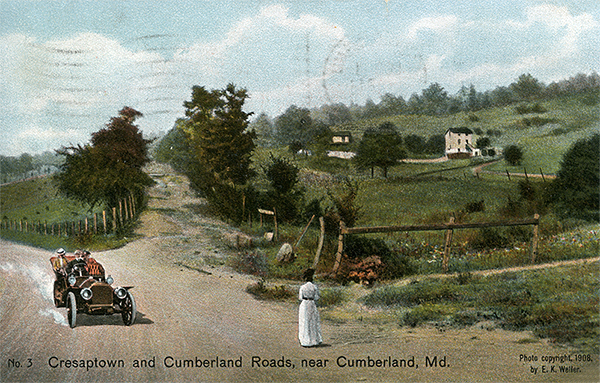

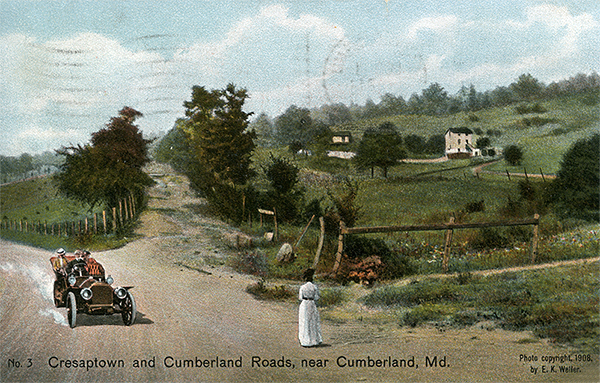

Cresaptown and Cumberland Roads. The old Braddock Road at the foot of Wills Mountain crossed at or near the present junction of the old Cumberland (or National) Road with the Cresaptown Road, thence proceeding westerly in a line almost parallel to the Old Cumberland Road, across Wills Mountain. No scar at this point is visible, but the course of the road is well defined. Major Chapman in May 30, 1755, with a detachment of 600 men marched at daybreak and began the ascent of Wills Mountain. [Lacock] |

From Fort Cumberland westward Braddock had to make a road for his troops across mountains divided by ravines and torrents, over a rugged, desolate, unknown, and uninhabited country. The history of the construction of this road and a description of its course it is the purpose of this paper to set forth; for the growing interest with which the routes of celebrated expeditions are coming to be regarded, and the confusion that attends the tracing of such routes after a lapse of years, make it altogether fitting that the road by which the unfortunate Braddock marched to his disastrous field should be surveyed, mapped, and suitably marked while it is yet possible to trace its course with reasonable definiteness.

In any discussion of this subject three things should be borne clearly in mind: (1) the irregular topography and mountainous nature of the country through which the road had to be built, for there mere as many as six ranges of the Alleghanies to be crossed, besides other mountain elevations and passes that presented as great and serious difficulties; (2) the wooded character of the country; (3) the fact that the road had to be constructed by the soldiers of the army. It is noteworthy that the road which Braddock made followed very closely the course of the so-called Nemacolin Indian trail,[9] and that it was used as a pioneer road as far west as Jumonville until late in the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

|

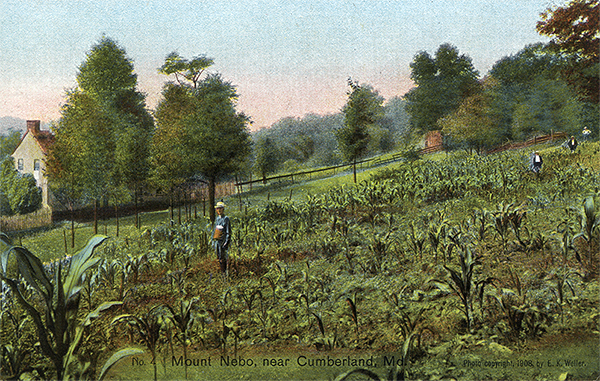

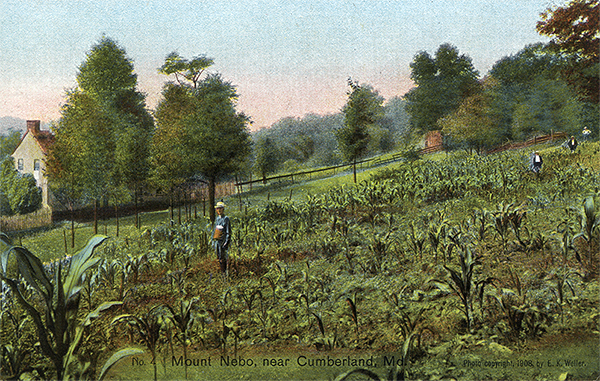

Mount Nebo. On the north side of the Old Cumberland Road, and about 90 feet from the Mount Nebo School Building - later known at the Steel House - the distinct trace of Braddock's Road is to be seen. A short distance from this point the road enters the wooded part of Wills Mountain. It is here that the real difficulties in the construction of the road began. [Lacock] |

On May 30, a detachment of six hundred men commanded by Major Russell Chapman set out to clear a road twelve feet wide from Fort Cumberland to Little Meadows, twenty miles away; but in spite of some work previously done on Wills Mountain, just west of the fort, they had so great difficulty in passing the elevation that on the first day they got but two miles from the starting-place. In the process, moreover, three of their wagons were entirely destroyed and many more shattered.[10]

Of the road from old Fort Cumberland to the foot of Wills Mountain no trace can be found today, but it seems probable that its course lay along what is now Green Street in Cumberland. There is, however, just as good and as direct a route from the camp by way of Sulphur Spring Hollow, past the present Rose Hill cemetery, with an easy, ascending grade to the ridge of the spur of Wills Mountain, and so on to a point at or near the intersection of the Sulphur Spring, Cresaptown, and Cumberland roads.[11] Something might be said in support of this route. Nevertheless, the former as the direct way to reach the fording at Wills Creek the old trading-post at this point; and it was the way west known to the Indians.

At the foot of the mountain the road proceeds westerly, parallel to the Cumberland Road but ninety feet north of it, to a point opposite the old Steel House.[12] At this spot the first depression or scar of the Braddock Road can be seen today.

|

Summit of Wills Mountain, near Cumberland, Md. From Mount Nebo Braddock's Road veers away somewhat to the north from the Cumberland Road in a series of absolutely straight lines, none of which vary more than five (5) degrees to the top of the mountain. The scar on the mountain is very marked in places. Great difficulties were encountered in the construction of the road over the mountain. Three waggons were entirely destroyed the first day and many more were badly shattered. [Lacock] |

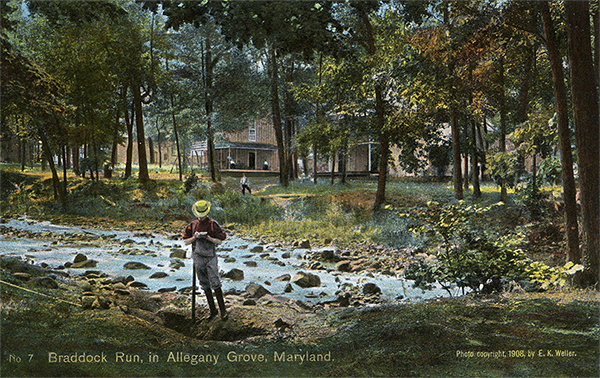

A short distance farther on, the road enters the wooded part of Wills Mountain. At a distance of about four hundred feet westward it veers away to the north from the old Cumberland Road, following to the top of the mountain a succession of absolutely straight lines, no one of which varies more than five degrees from the preceding line. Thence the course bears to the south and joins the Cumberland Road opposite the old Steiner House (now owned by Frederick Lang) in Sandy Gap,[13] about a mile and a half from the junction with the Cresaptown road. To this point the route may be traced with very little difficulty. From Sandy Gap it follows the present course of the old Cumberland Road for about seven-tenths of a mile,[14] crossing the George's Creek and Cumberland Railroad and the Eckhart branch of the Cumberland and Pennsylvania Railroad, to the house now occupied by Edward Kaylor, 380 feet from the latter railroad crossing. Here the line leaves the old Cumberland Road and runs due west four-tenths of a mile, passing under the front or southwest corner of the new house recently built by William Hendrickson, then fording Braddock Run in Alleghany Grove south of Lake View Cottage, thence running through Alleghany Grove to the Vocke road 440 feet south of its intersection with the National turnpike and 700 feet north of the now abandoned part of the old Cumberland Road, and keeping on still in the same straight line 1100 feet westward to the turnpike. So great was the difficulty experienced by the advance party in passing this mountain that General Braddock himself reconnoitered it, and had determined to put 300 more men at work upon it when he was informed by Mr. Spendelow, lieutenant of the seamen,[15] that he had discovered a pass by way of the Narrows through a valley which led round the foot of the mountain.[16] Thereupon Braddock ordered a survey of this route to be made, with the result that a good road was built in less than three days, over which all troops and supplies for Fort Cumberland were subsequently transported.[17]

|

Sandy Gap, near Cumberland, Md. This photo shows the intersection of the old Braddock Road with the old Cumberland Road in Sandy Gap, on the western slope of Wills Mountain, opposite the old Steiner house, now owned by Frederick Lang. This spot is bare of timber and can be distinctly seen from Big Savage Mountain. [Lacock] |

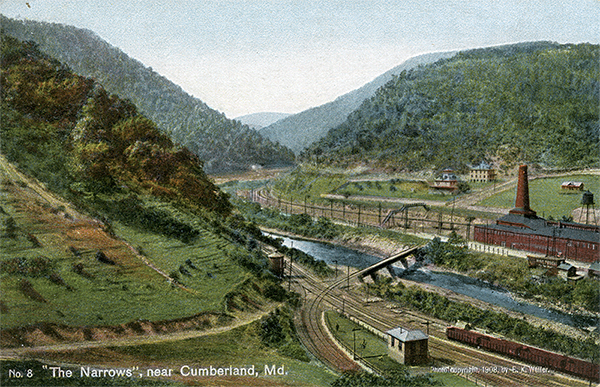

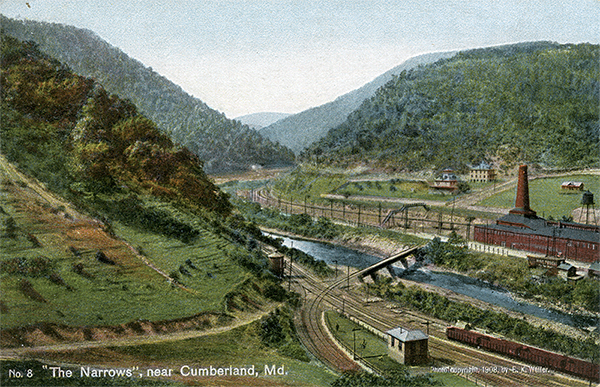

Every endeavor of the writer and his party to locate this new road through the Narrows and round Wills Mountain proved fruitless. Of approaches from Fort Cumberland to the Narrows over which an army with baggage trains could pass, four, and only four, were possible.[18] (1) One could cross Wills Creek at the ford or bridge near its mouth,[19] and then go up the left or eastern bank of the stream;[20] (2) one could pass down the decline back of the present Alleghany Academy to the creek, and then follow the shore on either side, fording at the most convenient point; (3) one could go drown the sloping ground northward from the fort, reaching the creek about where the cement mill now stands, and then go up the creek as in the second route;[21] (4) one could follow Fayette street and Sulphur Spring valley to the cemetery, and thence turning abruptly to the right go down a little valley to the Narrows, where a crossing of the creek would be immediately necessary. A high bluff, or 'stratum,' running down to the very water's edge of the creek on the right bank of the stream at the eastern entrance to this gap makes it almost unquestionable that the beginning of the pathway through the Narrows was on the left, or eastern, bank of Wills Creek.[22] The question is, did this pathway follow the left bank of the stream through the entire length of the gap, recrossing the creek near the mouth of Braddock Run; or did it recross it in the Narrows near the present location of the bridge over Wills Creek on the National turnpike, and thence follow the course of the turnpike to the western terminus of the Narrows? Judged by present conditions, the latter view seems the more probable; but it is impossible to do more than make a shrewd guess, for the construction of three separate railroads through this narrow valley has completely altered the banks of the creek and obliterated all traces of the road. In favor of the former contention it should be said that, within the memory of some of the older and more trustworthy citizens of Cumberland, there has been opportunity for the easy construction of a road on the left, or eastern, bank of Wills Creek.[23] Furthermore, at the entrance of the Narrows from the western end the stratum of hard white sandstone formerly extended to the waters of the creek.

|

The Narrows, near Cumberland. The difficulty experience by the advanced party under Major Chapman, caused Braddock himself to reconnoiter Wills Mountain. Mr. Spend low, Lieutenant of the Seamen acquainted the General, that in passing through the narrows he had discovered a valley leading around the foot of Wills Mountain. In two days the road was built intersecting the other road in the neighborhood of Allegany Grove. It was through the narrows that Braddock's main force and supplies began to pass on June 7. The present National Road passes through the narrows of Wills Creek along Braddock's Run. The entrance to the narrows as well as the narrows themselves present one of the most beautiful scenes in the Alleghenies. (See Nos. 3-7) [Lacock] |

Although the ground between these two obstructions to the Narrows on its right bank might have afforded a good roadbed, yet undoubtedly they proved to be obstacles that Braddock's engineers, with the appliances which they had at hand, could not easily surmount. It is well known to the older residents of Cumberland that as late as 1873 the mass of boulders at the eastern end of the gap, lying along the right bank of the stream, were in their primitive condition when a wagon road was constructed by George Henderson, Jr., to join the Cumberland road on that side of Wills Creek. On the contrary, the left bank presented no such difficulties in the way of road-building; and a careful examination of the ground through the entire length of the gap cannot fail to convince one that in Braddock's day there was opportunity for the easy construction of a road on that side.

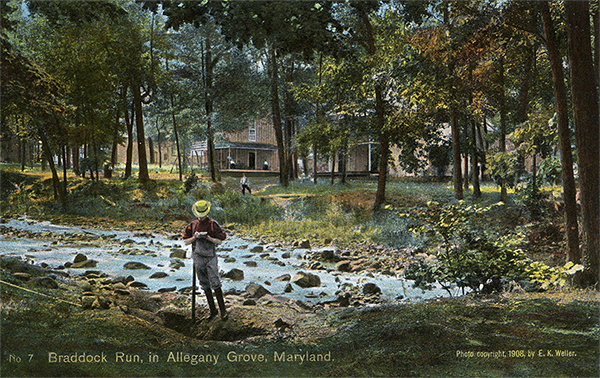

After leaving the gap the road turned into the valley of Braddock Bun; but the difficulty of finding present traces of it at this point seems almost insuperable on account of the character of the valley itself. The methods employed by Braddock's engineers in laying out the road indicate that its course was probably that afterwards followed by the National turnpike to a point near the northwest corner of the Alleghany Grove Camp Ground,[24] just beyond which and south of the turnpike is a distinct hollow or trench. The neighborhood of Alleghany Grove was unquestionably the place of the first encampment, Spendelow Camp.[25]

|

Braddock Run, in Allegany Grove, Maryland. The old Braddock Road from Sandy Gap follows the course of the old National Road to Allegany Grove , one mile distant. In this beautiful grove traces of the old Braddock Road are distinctly discernable. One of the most picturesque scenes is the fording of Braddock's Run. On the north side of the ford is Lake View Cottage. On the north and south sides of this grove respectively run the old National Road and the present National Road laid out in 1835. Major Chapman, on May 30, 1755, marched but two miles, hence must have camped here at Allegany Grove. [Lacock] |

Footnotes

[6] Braddock to Sir Thomas Robinson, Olden Time, II, 237. See also Hulbert, Historic Highways, IV, 68; and Franklin, Works (Bigelow ed.), I, 251, 257.

[7] Orme Journal, 315. See also Thomas Balch, Letters and Papers relating to the Provincial History of Pennsylvania, 34-35.

[8] See Burd Papers (Mss.) in the library of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. At the time of Braddock's defeat this Pennsylvania road was completed to the summit of Alleghany mountain, some 20 miles beyond Raystown, now Bedford, Pa. (see Pennsylvania Colonial Records, VI, 484-485). In 1785 General Forbes constructed a road (now commonly known as the Forbes Road) from Bedford to Fort Duquesne. This route runs parallel to the Braddock Road, though many miles north of it.

[9] 'Hulbert, Historic Highways, II. 89-91. In 1753 the Ohio Company had opened up this path or trail at great expense; and in 1754 Washington had repaired the road as far west as Gist's Plantation (Mt. Washington). See Washington, Writings (Sparks ed.), II. 51.

[10] Orme Journal, 323-324.

[11] The construction of the Cumberland Road was authorized by an act of Congress, approved March 29, 1806, and entitled 'An Act to regulate the laying out and making a Road from Cumberland, in the State of Maryland, to the State of Ohio' (United States, Statutes at Large, Il, 367). By the provisions of the act the President was required to appoint, by and with the advice and consent of the Senate, three discreet and disinterested citizens to constitute a board of commissioners to lay out the road. The men selected were Thomas Moore and Eli Williams of Maryland, and Joseph Kerr of Ohio.

In their second report, under date of January 15, 1808, the commissioners show that the new road followed only a very small portion of the Braddock Road. 'The law,' runs the document, 'requiring the commissioners to report those parts of the route as are laid on the old road, as well as those on new grounds, and to state those parts which require the most immediate attention and amelioration, the probable expense of making the same passable in the most difficult parts, and through the whole distance, they have to state that, from the crooked and hilly course of the road now traveled, the new route could not be made to occupy any part of it (except an intersection on Wills Mountain [Sandy Gap], another at Jesse Tomlinson's [Little Meadows], and a third near Big Youghiogheny [Somerfield], embracing not a mile of distance in the whole) without unnecessary sacrifices of distance and expense' (Executive Document, 10 Cong. 1 sess., Feb. 19, 1808, 8 pp.).

On November 11, 1834, the new road through the Narrows was opened for travel, the citizens of Cumberland, Frostburg, and the vicinity celebrating the occasion in an enthusiastic and elaborate manner (Lowdermilk, History of Cumberland, 336).

[12] This was formerly the building of the Mount Nebo School for Young Ladies.

[13] This point of intersection may he further verified by reference to the first report (of December 30, 1806) made by the commissioners who laid out the Cumberland Road: 'From a stone at the corner of lot No. 1, in Cumberland, near the confluence of Wills Creek and the north branch of Potomac River, thence extending along the street westwardly to cross the hill lying between Cumberland and Gwynn's Six Mile House, at the gap where Braddock's Road passes it' (Executive Document, 9 Cong., 2 sess., Jan, 31, 1807, 16 pp.).

[14] It probably follows the turnpike here in order to avoid a very deep hollow. This conclusion of the writer is confirmed by the resurvey of Pleasant Valley patented to Evan Gwynne on October 5, 1795, which calls for 'a water oak standing above the three springs that break out in Braddock's Road' (Deed from Evan Gwynne to Joseph Everstein, May 27, 1834, recorded in Liber R, folios 95-96, in the office of the clerk of Allegany County, at Cumberland. Maryland). These springs are a few rods west of James H. Percy's house, which is on the Cumberland Road.

[15] The Honorable Augustus Keppel, commodore of the fleet, had furnished Braddock with a detachment of thirty sailors and some half-dozen officers to assist in the rigging, cordages, etc. These seamen proved of valuable aid to the expedition in getting the wagons and the artillery down the mountain.

[16] Orme Journal, 324.

[17] Orme Journal, 324; also Seaman Journal, 381-382. For reasons not easy to understand, the Cumberland Road was laid out along the more westerly deflection over Wills Mountain by the way of Sandy Gap, instead of by the natural and more favorable route through the Narrows of Wills Creek. In 1834, however, it was changed to the latter location, and remains the line of the present National turnpike.

[18] The writer has interviewed many of the reliable and trustworthy citizens of Cumberland on this point. To Robert Shriver and J. L. Griffith, respectively president and cashier of the First National Bank of Cumberland, and to the late Robert H. Gordon, one of the leading attorneys of the town, he owes special thanks for their painstaking interest, given at the expense of much valuable time, in aiding him in his attempt to discover the route of the army out of Cumberland. Mr. Shriver, who has made an extensive study of the course or the road from Fort Cumberland to the Narrows, thinks that the weight of evidence favors a route from Fort Cumberland along the gradually sloping ground northwestward to a point on Wills Creek about where the cement mill now stands. From here the road would have been easy, comparatively short, and almost level for the greater part of the distance to the eastern end of the gap, where there would evidently have been a favorable opportunity to ford Wills Creek near the mouth of one of its tributaries. Much might be said in favor of this contention; but, unfortunately, it has thus far failed to yield any results that look toward a definite and authoritative identification of Braddock's line of march.

[19] It is worthy of note that the bridge was in course of construction at least twelve days before the road through the Narrows was completed (Seaman Journal, 379).

[20] See Shippen's manuscript draft of 1759, in the library of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania; map in Orme's Journal, op. 282; and a map in Hulbert, Historic Highways, IV, op. 20. These maps, though necessarily drawn on a small scale, give color to the theory of this route.

[21] See Washington's manuscript sketch of Fort Cumberland made in 1758, in E. M. Avery, History of the United States, IV, 207.

[22] In 1863 Mr. Robert Shriver made a most excellent photograph of this point, which shows the stratum in its primitive condition.

[23] See Lowdermilk, History of Cumberland, 137; also Searight, The Old Pike, 64, 71 ff. G. G. Townsend of Frostburg, road engineer for Alleghany County, Maryland, has an old blue print, made before the railroads were built, which shows on the left, or eastern, bank of Wills Creek a wagon road running through the Narrows and crossing the creek near the mouth of Braddock Run.

[24] The three engineers who accompanied Braddock's expedition (Seaman Journal, 364) made striking use of a series of absolutely straight lines in laying out the road, except where the fording of a river required a tortuous route, or where the topography of the country was such as to render their plan utterly impracticable. This device, which impressed itself upon the writer and his party as they were crossing wills Mountain, afterwards proved of great value to them in their efforts to pick up the road where traces of it were completely obliterated for rods at a time in cultivated fields.

[25] Orme Journal, 327. In fixing the several encampments the writer has been aided to some extent by the maps already published, but chiefly by Orme's journal, which records the number of miles of each day's march with great accuracy, and by the topographic sheets, without the aid of which neither the road nor the encampments could have been so definitely located.

Previous Page | Next Page | Introduction | Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4 | Part 5 | Part 6

View user comments below.